In 1929, the demolition of slums in an impoverished part of London known as “Little Hell” was a popular spectacle; 85 years later, a demolition of tower blocks in Glasgow will be part of the celebrations for the Commonwealth Games – but it faces a barrage of criticism. What lies behind the production of demolitions for public entertainment?

In 1929, the demolition of slums in Somers Town, an impoverished part of London behind Euston Station known as “Little Hell”, was turned into a spectacle. Huge, detailed models of the pests that infested the old housing – a cockroach, a rat, a flea and a bedbug – were made in cardboard and straw and piled up in a heap of rubble and half-demolished buildings, an audience gathered, the press were there to report on it and a retired general was brought in to set light to the pyre. The event provided a symbolic destruction of the houses and by extension the eradication of the area’s appalling living conditions, some of the worst in the capital at that time. Ben Campkin in his book Remaking London: Decline and Regeneration in Urban Culture describes it as a “physical, performative and visually impressive act”.

The old slums were replaced by bright new social housing developments by the local council and St Pancras House Improvement Society, a housing association run by middle-class activists. The publicity for the demolitions was seen as a way of heralding a new era of hope and regeneration. There is no hint in the reports of the day that the demolitions were seen as anything other than positive – no suggestion they were criticised as the actions of misguided do-gooders and money-grubbing developers, or regretted by people who had lost their homes and community.

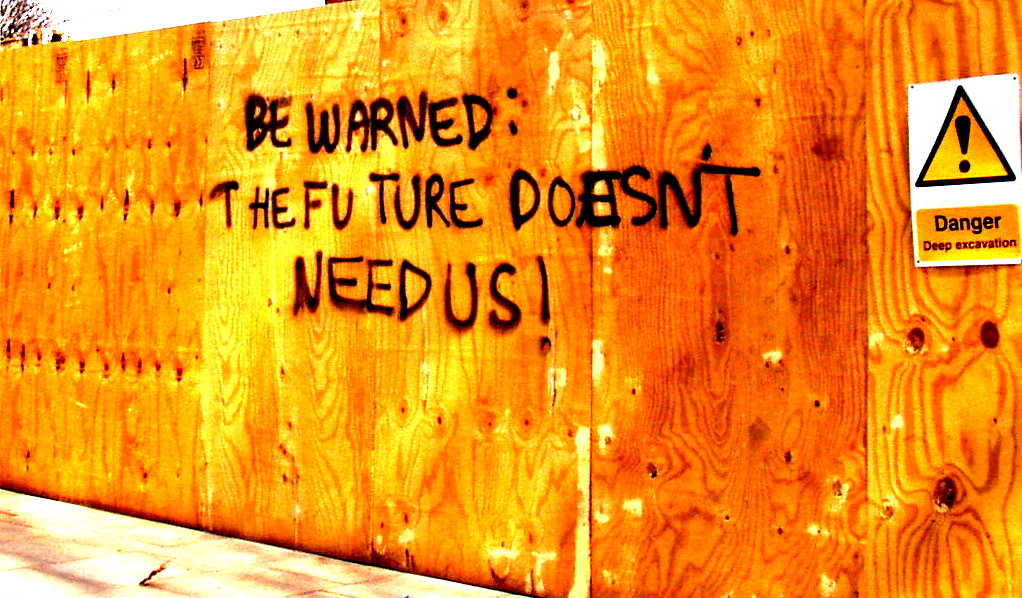

Eighty-five years later, a new demolition-spectacle is being planned by a housing association. Again, an audience is being gathered to witness the event and press will be there to document it for a wider public. Again, a notorious housing estate – this time, the Red Road towers in Glasgow (pictured above). The plan is to blow up five of the remaining six Red Road tower blocks, with film of the explosions shown live on giant screens in Celtic Park for the opening of the Commonwealth Games on 23 July.

The reasoning for the spectacle is very much the same as that of the 1929 conflagration in Somers Town. Quoted in the Guardian, David Zolkwer, artistic director for Glasgow 2014, said: “It’s a bold and confident statement that says ‘bring on the future’.”

But this time there has been a flood of protest.

From Scottish newspaper the Herald:

While organisers said the demolition, the brainchild of creative teams within the organising committee, will make an “unforgettable statement” about Glasgow’s history and future, destroying buildings that were once home to thousands to provide a spectacle has been described as crass and offensive by critics.

Signatories to the petition [against the spectacle] have described the idea as vulgar, callous, arrogant and ghastly. Nicola Page, who spent her childhood in Red Road, wrote: “The world is now invited to laugh at and applaud the final death of the home that so many will mourn.”

The petition states that the demolition should instead be carried out “with dignity” and that the current plan would send out a message to asylum seekers in the one remaining tower that “they are not human enough to deserve decent housing”.

Alison Irvine, author of a novel about the Red Road estate, described the spectacle as “crude, insensitive, blunt” and accused the Glasgow 2014 committee of “trampling over the memories of people”.

Writing in the Scotsman, Joyce McMillan suggested the context of the spectacle, as part of the Commonwealth Games celebrations, “seems as uneasy and tasteless as it is bold”. She points out some other reasons for the hostile reactions:

The embrace of old and disused industrial spaces during 1990 was essentially an act of creative reinvention, and of imaginative tribute to the past; the spaces themselves were often beautiful, with a terrific melancholy grandeur, and the work created there was often breathtakingly powerful.

The demolition of Red Road, by contrast, is an act of outright destruction, and a highly ambiguous one. The flats may have been notorious … their design and construction was certainly part of the long decline of paternalistic municipal socialism, a shameful triumph of theory, ideology and influence over grass-roots democracy and common sense.

… It seems both problematic and strange to ask people to stand and cheer the destruction of such a large area of social housing at a time when the nation is in desperate need of cheap, affordable homes, and difficult to trust that the same council which built the flats in the first place, and its offshoot housing company GHA, will automatically replace the flats with something better.

It’s a view that contrasts with that of the organisers. According to Eileen Gallagher, the chair of Glasgow 2014’s ceremonies committee: “By sharing the final moments of the Red Road flats with the world, it is proving it is a city that is proud of its history but doesn’t stand still.” Gallagher describes the demolition-spectacle as a “celebration” of Glaswegians’ “tenacity, their genuine warmth, their ambitions”.

Perhaps in 1929 London, the idea of demolition as a bold celebration, of saying “Bring on the future”, held no irony and provoked no cynicism. Indeed, the estates that replaced the filthy, pest-ridden slums of Somers Town were designed by idealistic (if paternalist) architects and social workers who thought carefully about residents’ needs. Eight decades on, Britain has had more than enough experience of housing developments put up cheaply and quickly, motivated by profit, and now we are sceptical of grand statements of intent.

And maybe in 1929, there were also people resisting change, mourning the end of an era and the destruction of their homes; it’s just that they didn’t have a voice.

+++++++++

UPDATE 13 April

The demolition of the Red Road flats as a spectacle for the Commonwealth Games has been scrapped for “safety reasons” after an online petition protesting against it attracted thousands of signatures. From the Guardian:

In a statement, the Glasgow 2014 chief executive, David Grevemberg, said: “The demolition of Red Road will now not feature as part of the opening ceremony.”

Grevemberg said the decision was taken after opinions were expressed that “change the safety and security context”.

I wonder whether the sheer scale of the spectacle planned was what tipped the balance of disapproval – the Glasgow Housing Association which owned the flats had claimed 1.5bn people around the world would be watching the collapse of the 30-storey blocks on TV. Behind the display were the same good intentions that motivated the Little Hell demolitions – Grevemberg claimed the idea was to tell “the story of Glasgow’s social history and regeneration” and the housing association said the demolition would “serve as a respectful recognition and celebration of the role the Red Road flats have played in shaping the lives of thousands of city families”. But instead of respect and celebration, the protesters spoke of the act as disrespectful, “disuniting”, ruthless and insulting; in the contest of emotions, their anger has won the day, and presumably the demolitions will go ahead out of the spotlight.

Some links

• Florence Foster talks about growing up in Little Hell in the early 20th century

• Photos on Flickr of present-day Somers Town

• The demolition of part of Red Road flats in 2012 – video

• Short history of Red Road flats